Robert W. Young, writing in Black Belt magazine, on Kathy Long's cross-training. Her contention is that one martial art doesn't prepare you adequately for what you may encounter. I have to agree.

I've found that most of the students at my school (sold in 1996) that had just trained in TKD didn't have a clue when it came to fighting, versus just sparring. That was one of the reason I taught a Muay Thai/boxing class on Saturdays - it prepared them for contact, and to fight back after getting hit, versus stopping (a la point fighting). What wasn't addressed was ground fighting, or stand-up grappling. They're still a weak area for me, one I started to improve upon when I began my study of Judo. My attendance, years ago, at a Wally Jay seminar, then subsequent exposure to JuJitsu convinced me of the deadly quality of throws, plus the ability of grappling stylists to control a subject and ratchet up the pain when needed, versus just breaking a skull, knees, or ribs as I would have to do. I was actually in awe after watching two of the Wally Jay seminar participants who were Judoka-they were practicing throws, and I knew that that was what I needed to learn next to become a more complete martial artist.

My focus now is on becoming a strong exponent of all the modern warrior skills-striking, throwing, grappling & submissions, knife, stick, gun, and defensive strategy.

On to the excellent article:

Sooner or later, it happens to every martial artist: You have devoted the past 10 years to honing your skill in isshin-ryu karate—or Shaolin kung fu or muay Thai kickboxing or whatever—and you think you are a pretty good fighter.

Then one day you spar with a practitioner of a different style, and he succeeds with so many defensive and offensive techniques that it takes you completely by surprise. You throw your best roundhouse kick, but he just absorbs it and slams you to the mat. You poke at his head gear with your tiger-claw strike, but he just slips to the side and locks your arm, then sends you sailing over his hip.

You never even see his counterattacks coming, but afterward you thank your lucky stars the encounter happened in the gym and not on the street.

For some martial artists, such an experience elicits nothing more than a hokey attempt at rationalization: “Our sparring rules don’t permit throwing. The mat was so soft that I couldn’t push off to throw my reverse punch. I didn’t know he was going to grab my legs and take me down, but I’ll be ready next time.”

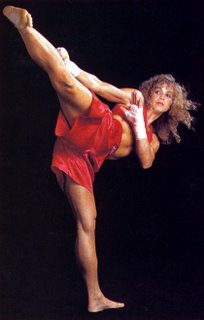

But for more open-minded practitioners, such as former kickboxing champion Kathy Long, such experiences open their eyes to a whole new world of self-defense training—in a different but complementary martial art.

... Long has invested time in so many styles because she believes that martial artists interested in self-defense should strive for maximum versatility. “It’s like when you get into kickboxing: If you have a really good jab and nothing else, you have a deficit,” she says. “If you’re going to be a well-rounded martial artist, you can’t study just one style. Every style has holes and deficiencies, and you have to be able to fill them.”

... You can’t do just one style and expect it to be as destructive as you’d like to be in self-defense.”

Kicking and punching are obviously important for self-defense, but so is ground work.

“You should learn it [ground work] if you want to be a well-rounded martial artist—and that’s the key phrase right there. If you just like one style, then do it. There’s nothing wrong with that. But if you want to be well-rounded, you can’t take just one style. Take san soo, mix it with jujutsu, kickboxing and Philippine martial arts—either kali or escrima, with empty hands, sticks and knives—and you’ll be set.”

Such flexible skills are needed because you never know what kind of a situation may arise. “I’ve seen the way people who don’t know martial arts fight,” Long says. “There are times when they end up on the ground, and there are times when they stand there crazily throwing punches at each other without rhyme or reason.”

... A frequently mentioned fear of cross-training martial artists involves becoming what is commonly referred to as a “jack of all trades but master of none”—in other words, a person who has a superficial knowledge of several styles but advanced skill in none.

“Why is it bad to have a good basic grasp of three or four martial arts and not be a master of any of them?” Long asks. “People who work don’t have time to dedicate five

or six years to every style they want to get into.”Cross-training is the best way to overcome that obstacle and prepare yourself for any eventuality, she adds.

No comments:

Post a Comment